Iconic species

South Africa's oceans have a rich diversity of life.

These are some of the most charismatic.

These are some of the most charismatic.

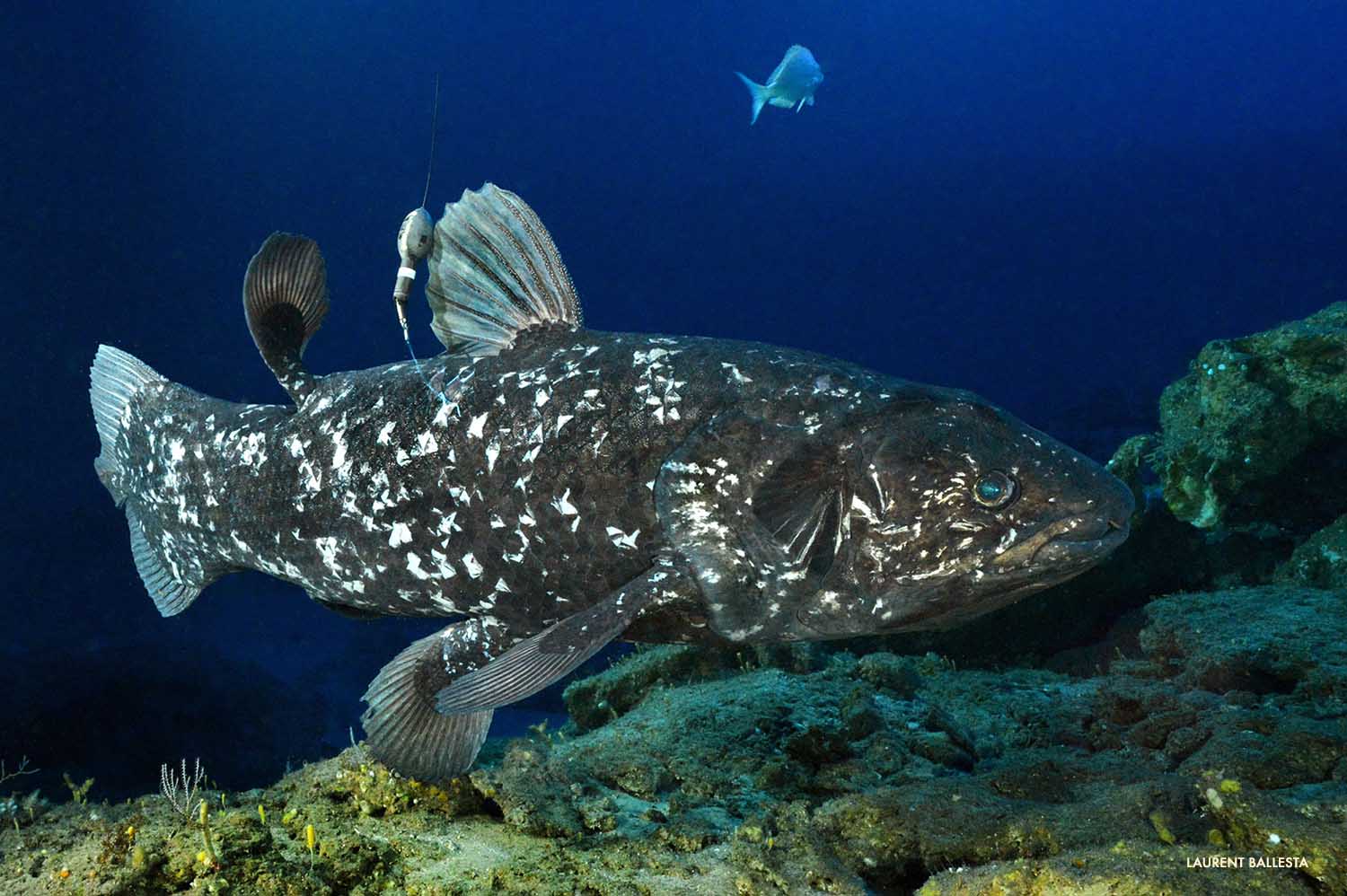

These ancient fish were alive during an era when dinosaurs roamed both seas and land. There are two species, the Indonesian and the West Indian Ocean coelacanth, of which the latter is found in South African waters.

Peter Timm and his two deep diving students, Peter Venter and Etienne Le Roux, were the first scuba divers to see coelacanths in their natural environment when they observed three individuals on the rocky margin of Jesser canyon at Sodwana Bay in the proposed iSimangaliso MPA in October 2000. Since then, deep divers and scientists have documented at least 30 individuals in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, South Africa’s first World Heritage Site in northern KwaZulu-Natal. Each coelacanth is identified by its unique white spot patterns on the dark scales of this ancient group of lobe finned fishes.

Dr Kerry Sink, a scientist at the South African National Biodiversity Institute has followed the lives of these animals over the last 18 years, maintaining a catalogue that tracks sightings of each individual seen by diver, Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), and through the window of a yellow submarine. The Jago submersible team have documented 145 individual coelacanths in their many expeditions in the Comoros Islands where the second coelacanth known to science was reported. Sodwana’s colecanths all have names such as Jessie known from Jesser Canyon, Sidney and Twilight from Wright Canyon and Shaka and Nandi from Chaka Canyon. In 2014, scuba divers found the shallowest record of a coelacanth at 54m in a cave at the head of Diepgat Canyon known as “the box”. This large coelacanth is called Pandora.

Jessie, a very large coelacanth was one of the first coelacanths photographed by deep divers in Jesser Canyon and has been seen many times in nine different years between 2002 and 2016. Female coelacanths grow to larger sizes than males. We know this from coelacanths caught accidentally by oilfish fishermen in the Comoros and more recent accidental captures in deep set shark gillnets in Tanzania.

Jessie the Coelacanth (Laurent Ballesta)

Its Jessie’s large size at about 1.8 m that led us to think that she is a female with all male coelacanths reported to be smaller than 1.6m with females reaching a maximum size of 1.8m and 98 kg. Coelacanths give birth to live young in a style of reproduction known as ovovivipary which means that their eggs mature within the body and are nourished by a yolksac rather than a placenta. Coelacanth eggs are as about the size of an orange and babies are expected to be born at a size of about 40cm. The smallest coelacanth seen to date at Sodwana is “Tot” (Individual 30) at a size of 1 metre. “Tot” seen only once in 2013 was accompanied by Grant “Coelacanth 4” named after the expert deep diver skipper Grant Brockbank from Triton Dive Charters. Jessie and Grant have often been seen together although Jessie has been seen with 9 different individuals over the last seventeen years. Jesser was last seen by deep diver Eve Marshall on 16 March 2016.

Noah is named for the distinct arc (semi-circle) pattern on both sides of his (or her) body. This coelacanth was first seen during the 2003 Jago submersible expedition but has been seen by divers (including famous deep diver Richard Pyle who pioneered deep decompression stops known as Pyle stops), Remotely Operated vehicle in 2005 and 2011 and other trimix teams in 2012 and 2013.

Noah the Coelacanth (Peter Timm)

Noah was last seen by a Japanese team in July 2018 who left a camera in a known coelacanth cave overnight and captured Noah and a ragged tooth shark in the cave. Noah has a distinct white spot on his snout. He is one of 5 coelacanths to be sighted in both Jesser and Wright Canyon which are about 4km apart.

“Eric eyelashes” is a prettily marked coelacanth first photographed by one of the French trimix divers, Eric Bahauet, in 2009. Eric has been seen only four times but has taught us some new coelacanth secrets! Eric’s name is not just about the eyelash-like markers on the left side of “his” face or his first photographer but also Captain Eric Hunt, a central figure in the coelacanth story.

Eric the Coelacanth (Laurent Ballesta)

Eric Hunt alerted Professor JLB Smith to the presence of the coelacanth in the Comoros Islands after seeing his pamphlet advertising the “Hundred pound fish”. In 2013, the French dive team under the leadership of Laurent Ballesta (Andromede Oceanologie) tagged Eric with a pop up satellite tag that was recovered 9 months later 12 km north of where Eric was tagged (read more). We haven’t seen Eric since 2013 but perhaps this might be because Eric is living in a new coelacanth location that neither scientists nor divers have explored offshore of nine mile reef where his tag emerged at 1 am in May 2014. Eric ranged between 75 and 392 m depth and spent long periods at a depth of 150 m. We need to go look for caves in this depth range! Eric has been seen in three different caves in Jesser canyon.

South African waters are home to more than 30 species of sharks. These range from the Hammerhead Sharks that in the tropical waters of east coast to the tiny Puffadder Shysharks that roam the kelp forests along the southwest coast.

South Africa’s sharks are a major attraction for television crews such as BBC and National Geographic. Local and international tourists flock from far to see these sharks for their own eyes. Great white shark tour operators in False Bay and Gansbaai generate enormous revenue every year. Aliwal Shoal is one of the most popular diving destinations for shark enthusiasts, as they come to see the spectacular aggregations of Raggedtooth Sharks and the large numbers of Blacktip and Tiger Sharks. The offshore expansion of Aliwal Shoal, together with Protea Banks MPA, will protect important habitat for seven species of shark.

iSimangaliso MPA will protect Raggedtooth Sharks that use Quarter Mile Reef and the sanctuary at Leadsmans when they are pregnant. It is also the only area in South Africa where Silvertips, Grey Reef, White-tip Reef Sharks and Whale Sharks occur. The offshore expansion of the iSimangaliso MPA will further protect core tiger shark habitat.

A newly discovered gathering of giant guitarsharks in uThukela Banks is the first of its kind in the world. This proposed MPA is also a nursery area for hammerhead sharks. The existing Pondoland MPA is important for species such as Dusky Sharks and Bronze Whalers that migrate though this area during sardine run.

There are also a number of pelagic sharks that live in the open ocean ecosystems, including blue and mako sharks. Blue sharks will receive protection in the Orange Shelf Edge MPA and mako sharks in the Southwest Indian Seamounts MPA. Amathole Offshore MPA will provide protection to several shark species, including the small guitarshark.

This video shows the wide range of sharks you can see in South African waters - Sharks of South Africa.

Puffadder Shyshark (Steve Benjamin)

Hammerhead Shark (Steve Benjamin)

Whale Sharks occur in iSimangaliso MPA (Steve Benjamin)

The diversity of these large marine mammals in South African waters is remarkable, with over 40 species that depend on our rich coastal and open ocean ecosystems. The waters near Cape Town support the widest diversity, including five species of dolphin and three species of baleen whale, as it is the boundary between the cold Benguela ecosystem and the warmer Agulhas Current. The close continental shelf around Cape Town also means that some deep-water species like pilot whales are occasionally seen.

Cetaceans comprise two basic taxonomic groups, the mysticetes (filter feeding whales with baleen) and the odontocetes (predatory whales and dolphins with teeth). The term ‘whale’ is used to describe cetaceans larger than approximately 4 m in length, in both these groups and is taxonomically meaningless For example, the killer whale and pilot whale are members of the Odontocetes and the family Delphinidae and are thus dolphins, not whales.

Large super-pods of humpback whales feed off the coast offshore of Cape Town to Yzerfontein on their annual migration from the tropics to Antarctica. These are the largest groups of humpbacks known on Earth. Cape Canyon MPA protects these important feeding areas.

The seasonal Walker Bay MPA was designed to protect southern right whales that calve in these waters for three months of the year around spring. In a recent survey scientists recorded nearly 1400 whales the bay. De Hoop MPA provides additional protection to southern right whales and Addo Elephant National Park MPA will provide further protection up the coast in Algoa Bay.

Although most of the baleen whales have shown good signs of recovery from commercial whaling in the 20th century, particularly the southern right and humpback whales, others such as the Antarctic blue, fin and sei whales are still listed as Endangered or Critically Endangered on the South African Red list.

All the dolphin species are considered resident although many show some seasonal movements along the coast. The common and bottlenose dolphins that frequent the Transkei coast have become world-famous and feature in BBC's latest Blue Planet II. Amathole Offshore MPA provides protection for these two species along this stretch of coast. Namaqua National Park MPA provides protection for the playful Heaviside's dolphins.

Although dolphins were not subject to commercial whaling, their coastal distribution brings them into close contact with human activities such as fishing nets, anti-shark bather protection nets, pollution from rivers, noise and injury from ships and recreational boats etc.

The Indian Ocean humpback dolphin is the only dolphin listed as Endangered in South Africa. There have been clear decreases in sightings and group sizes throughout their range. Humpback dolphins are split into two populations in South Africa, one ranging along the Cape south coast and one on the northern KZN coast – combined there are likely only around 500 individuals of this species in the country, making them one of the rarest mammal species in the country. Find out more by visiting the Sousa Project. uThukela Banks MPA will provide protection for humpback dolphins.

For more information about whale and dolphin research in South Africa visit Sea Search.

Heavisides dolphins (Simon Elwin)

Southern right whale mother and calf (Peter Chadwick)

Southern right whales (Peter Chadwick)

Humpback whales (Steve Benjamin)

Common dolphins (Steve Benjamin)

Humpback whale breaches (Steve Benjamin)

Sea turtles are some of the most ancient reptiles still alive today and have been around for over 200 million years. They are adapted to living in the sea with flipper-shaped limbs and streamlined bodies, but must rise to the surface to breathe air. Five species of turtles are found in South African waters. The leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) and the loggerhead (Caretta caretta) turtles nest on the beaches of northern KwaZulu-Natal. The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is a non-breeding resident, while the hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) turtles occur as strays in our waters.

Unfortunately for turtles, the characteristics that helped them to survive over millions of years have made them vulnerable to the impact of humans. Turtles wander the oceans, on routes determined by evolution, returning to their natal areas (where they were born) to mate and lay their eggs. This has made them vulnerable throughout their life history. Pressures on turtles include entanglement with fishing gear or accidental capture, plastic pollution and, historically, population declines due to harvesting of eggs and adults for meat.

Nesting beaches along the northern KwaZulu-Natal coastline are protected by MPAs. Ongoing monitoring since 1963 has revealed remarkable results demonstrating the importance of beach protection for nesting female turtles. In 1966, fewer than 10 leatherback turtles nested on the Zululand coast. The average number of nesting leatherback females has now risen to more than 70 nests per year. The number of loggerhead turtles has risen even more spectacularly from less than 250 in the early 1960s to 1 700 nesting annually within the iSimangaliso Wetland Park.

The Agulhas Front MPA and iSimangaliso MPA protect important feeding grounds for these ancient reptiles, especially the leatherback turtle which is currently listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Leatherback turtles feed at the Agulhas Front

Green turtle (Steve Benjamin)

There are 350 species of seabird on Earth, of which 132 have been recorded in South Africa. These include terns, albatrosses, penguins, skuas, gannets, boobies, gulls, cormorants, shearwaters, storm petrels and frigatebirds. Twelve species are endemic to South Africa and include the African Penguin and the Bank Cormorant. The unique and dynamic ocean environment off South Africa is the reason for the high diversity of seabirds. Three oceans collide to create incredibly rich and productive feeding areas for these seabirds, that fly from all over the world just to feed here. Because seabirds are vulnerable to being eaten by land-based predators like foxes and caracal, they need islands to breed. Luckily for them and us, South Africa has plenty.

These endangered and charismatic creatures bring huge amounts of visitors to Boulders and Stony Point and feeding areas are protected by Table Mountain National Park MPA and Betty’s Bay MPA. These are the only coastal colonies in South Africa, the remainder breed on islands (Robben, Dassen, Dyer and St Croix). Both Robben Island MPA and Addo Elephant National Park MPA provide protection for these last refuges of African Penguins that have declined by 99% in the past century.

These exquisite seabirds breed only in South Africa and a few islands in Namibia. They are an attraction for tourists at Lambert's Bay but their stronghold is on Bird Island in the Addo Elephant National Park MPA where 60 000 pairs breed.

These are some of the most adaptable seabirds along our coastline. When food resources shift, so do they, with the ability to use different breeding sites from year to year. In 2017, 4500 pairs relocated from Robben Island to the roof of the Nedbank building in Cape Town!

There are no albatrosses that breed on the South Africa mainland, they prefer cooler islands farther south like the Prince Edward Islands. Sixteen species of albatrosses regularly fly to South African waters to feed. They travel all the way from remote islands near Antarctica and New Zealand. For instance, the entire world’s population of Chatham Albatrosses breeds on single rock 800 km east of New Zealand and flies all the way to the Agulhas Bank to feed. Wandering Albatrosses leave their chicks at the sub-Antarctic Prince Edward Islands to find squid near the Agulhas Front. Albatross populations have suffered from accidental bycatch by commercial longline fishing vessels, but recent mitigation measures have reduced mortalities by up to 90% in some industries thanks to the work of the Albatross Task Force.

To find out more about the important seabird research and conservation being done in South Africa, visit the Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology, BirdLife South Africa and SANCCOB websites.

Over 2,000 species of fish are found in the waters around South Africa; most are tropical and subtropical and about 16 percent are endemic, which means that they are found nowhere else in the world. Fish species range from tiny gobies to huge whale sharks, and include both bony fish and cartilaginous fish – the sharks and rays. Commercial, subsistence and recreational fisheries in South Africa catch more than 630 marine species, most of them fish species. Traditional methods of monitoring and management of fish species have proven to be inadequate for certain species and regulations are often difficult to enforce effectively. This has meant that the stock status of only 41 species is known. Of those 41 species, 25 are considered to be overexploited, collapsed or threatened.

Globally MPAs are increasingly being used as an additional management tool to ensure sustainable use of many of fish species, particularly slow growing, resident species. There is a substantial body of research that demonstrates the effectiveness of MPAs in fish conservation in South Africa. Most of this research has been undertaken in our coastal MPAs such as De Hoop, Tsitsikamma (the oldest), Dwesa-Cwebe, Pondoland and iSimangaliso. In all of these MPAs the abundance of linefish inside the zoned no-take areas is far higher than in the adjacent exploited areas and the size of many of the recreationally and commercially important linefish species is also significantly greater within the no-take areas. There is thus conclusive evidence that no-take MPAs help to protect important linefish species.

Many offshore MPAs contribute towards the management of commercially important fish species such as hake, kingklip and sole. The Agulhas Mud MPA protects some of the habitat of the Agulhas sole, while Port Elizabeth Corals MPA contribute towards the protection of kingklip, one of South Africa’s most valuable fishes that aggregate to spawn here. Protection of rough grounds in Brown's Bank Complex and Namaqua National Park MPAs will assist hake populations that spawn in these areas. Even highly migratory species like tuna benefit from MPAs. The Agulhas Front MPA is within an Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA) recognised for its role in the life history of tuna and other fishes. The Agulhas Bank Complex MPA provides protection for migratory species such as geelbek and resident linefish such as red stumpnose, red roman and spawning aggregations of endangered red steenbras.

Unlike humans and most mammals, whose breeding ability declines after a certain age, in many fish species, the older and bigger the females get, the more fertile and productive they become. Where fish are allowed to mature undisturbed in a no-take area, the returns increase exponentially as their number of offspring increases. These young fish can move outside the no-take area into exploited areas. This flow of benefits is known as the “spillover effect” where fish populations build up inside the MPA and eggs and larvae from the large breeding adults can restock fishing grounds. This is extremely important as fishermen can benefit directly from this spillover in adjacent exploited areas. In many ways it is similar to having money in a bank account which, if carefully managed, can grow and produce interest which can be sustainably used without plundering the capital.

Rock lobsters, prawns, langoustines and crabs are valuable fisheries resources. There is evidence that Marine Protected Areas can support fisheries management of rock lobsters through spillover. Lobsters have complex lifecycles and more work is needed to plan for protection of the connected areas where different life history phases of these high value resource species occur.

MPAs can help protect representative habitat for fisheries. The lace coral habitats where the endemic south coast rock lobster occur are protected in parts of the Amathole Offshore MPA. In shallow water, West Coast Rock Lobsters already receive some protection in the waters around Robben Island and protection for East Coast Rock Lobster. Muddy habitats in the Amathole Offshore MPA support several prawn species, crabs, langoustines, including the Deepwater Rock Lobster. Deep water crabs on the west coast are currently harvested as a bycatch in the trawl fishery have some protection in the Orange Shelf Edge MPA. South African scientists are working hard to understand the habitat preferences of the rich diversity of crustacean resources in South Africa.

uThukela Bank supports a diversity of crustaceans (ACEP)

Muddy ecosystems support burrowing crabs and prawns (ACEP Spatial Solutions)

Our South Coast Rock Lobster only occurs in South Africa (Jago submersible)

Corals are pretty... amazing. Most South Africans are familiar with the beautiful coral reefs in northern KwaZulu-Natal. In the warm light infused water of the Indian Ocean these sunlight powered communities support an amazing diversity of fishes and a thriving scuba diving industry that is a key aspect of South Africa’s marine tourism economy. Further offshore there are deep water corals in the twilight zone of the iSimangaliso MPA and some deeper water species in this area rely on both algae in their tissues to make sugars and also filter food from the water. Scientists are increasingly interested in coals in deeper water because of the evolutionary history of coral and algae symbiosis and because these deeper reefs may be increasingly important in this era of climate change. The globally important role of coral communities in iSimangaliso are recognized as vital to climate adaptation and mitigation. Management needs to ensure that anthropogenic stressors and disturbances on coral reefs are kept to a minimum to maintain and enhance coral reef resilience in the face of anticipated future warming events.

The warm and cool temperate reefs of South Africa also provide homes for corals particularly soft corals and seafans – many of which are found nowhere else on earth. Deep and cold water coral communities also occur in the outer shelf, shelf edge and slope all around South Africa although our knowledge of these species is still limited. This is an area of active research in South Africa. Deep water corals include stony corals (the same groups that dominate shallow coral reefs); soft corals including seafans, cauliflower and thistle corals; lace corals. Different species within all these groups occur on the west, south and east coast which means that the fragile ecosystems that support these deep water corals need protection in each region. Coral habitats are sensitive to activities that impact the seabed including bottom trawling, petroleum activities, mining and anchoring. Sedimentation including from poor catchment management, offshore drilling and mining and even trawling can affect deep water corals.

On the west coast Childs Bank protects unique coral communities on the rocky slopes. Although trawling has damaged corals in this area, remaining patches of corals on the steep slopes can support coral recovery. Live and fossilised corals have been collected in the vicinity of Browns Bank Corals that may hold important clues about South Africa’s climate past. The SWIS1 section of the Southwest Indian Seamounts MPA includes a range of deep water coral species and the steep area provides a range of oceanographic conditions to support climate resilience. The Port Elizabeth Corals MPA is a unique feature that includes hard and soft coral taxa from the slope. Amathole Offshore MPA includes a high diversity of lace corals and stony corals. Aliwal Shoal MPA and Protea Banks MPA support different hard and soft coral species in deep water with particularly surprising coral diversity and a high abundance of large black coral trees on the outer shelf reefs and shelf edge of uThukela Banks MPA.

Biodiscovery is the process of screening animals and plants for the presence of compounds useful to humans. Several laboratories in South Africa are looking for such compounds and once discovered, work on identifying its structure. They also investigate the enzyme pathways by which the compound has been made, and try to establish alternative ways by which the compound can be artificially produced. Drug discovery takes a long time with clinical trails needed to test effectiveness and safety of potential medicines.

South Africa's waters are filled with such a large diversity of life and some of these have provided remarkable biomedical discoveries. These include seaslugs and nudibranchs, seasquirts (ascidians) and sponges that have cancer-fighting compounds. The frilled or silver nudibranch Leminda millecra is found only on the south and east coast of South Africa and has produced compounds that fight oesophagal cancer. Sponges from Sodwana, the Tsitsikama area and Aliwal shoal have also produced amazing useful compounds with further work underway.

One of the most potent compounds ever tested against cancer comes from a very strange animal found only in South Africa’s ocean. This animal is known as a hemichordate (a small animal phylum that includes acorn worms and pterobranchs) and is a worm-like colonial animal that lives within a prickly network of jelly-like tubes. Named after our first government marine biologist John Gilchrist its scientific name is Cephalodiscus gilchristi and the famous compound which can inhibit tumour growth is called Cephalostatin 1.

The pink frogmouth is a recently described species that was filmed during the ACEP Spatial solutions cruise. A rare lionfish, a new species of hermit crab and many unidentified deep water corals have been observed. New work is underway to collect, identify and describe such species.

It took a long time for scientists who first observed large foraminera on the seabed to identify these ancient and strange animals. Foraminifera or “forams” for short are single celled animals that secrete shells. There are more than 4000 species known. Forams are important because they provide information about the age of rocks, provide knowledge about past environment and climate and have even been used to discover petroleum. Sand dollars, snails and fish include forams in their diet.

When divers showed scientists the curious 30 cm tall mounds of shell and gravel at 40-70 m depth at Sodwana Bay they also had no idea what made them. Coelacanth discoverer Peter Timm eventually photographed the beautiful tilefish who makes these homes on the seabed and noted that this fish is harder to photograph than a coelacanth!